Surfaces, Brushes and Brush Strokes

A fundamental human trait, which all artists must understand and overcome, is the almost primeval desire, when presented with a brush full of paint, to keep painting until we have emptied the brush. This message is reinforced for me every time I watch my six year old daughter painting. She just cannot stop. No matter how hard I try to manipulate her by limiting her colours or only giving her small brushes, she ends up spreading all the paint I give her all over the paper surface until it is a mass of brown gunge. It's fine for her of course, she draws great pleasure from both the process and the result so no harm is done, but for me it is a different story.

To ensure that I am satisfied with my results I select my painting surface and brushes very carefully to make sure that the conscious me is in full control of where the paint goes.

The catch-22 of selecting a painting surface

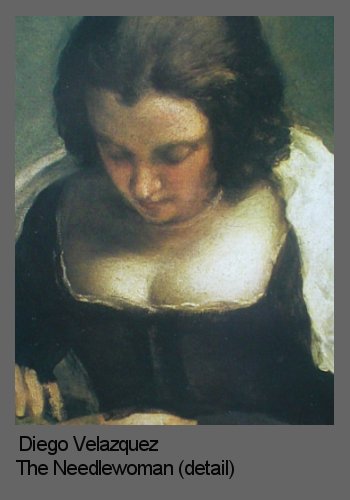

In the early stages of a portrait painting, when they do not yet know their way around it, most artists like to keep the colour on their painting surface fairly thin to stop themselves from putting paint where it should not be going. This is called painting from ‘lean to fat’ and artists often do it because, with the right brush selection and application, they can get away with painting corrections over thin paint quite easily (see below). Though I try to put a small amount of paint on my brush at the very beginning, I still find it incredibly easy to put more on than I personally want, so I have another trick up my sleeve. I purposely work on a canvas surface which has quite a deep weave so that the cavities in the weave absorb any excess paint. The catch-22 of this painting surface comes later on when I have got the basic shadows and forms in and I am ready to start adding more paint with confidence. Then my brush does not always move across the canvas surface as smoothly as I would like it to. The weave absorbs paint when I don’t want it to, and sometimes I have to repeatedly take my brush back for more paint. I have heard artists, such as Rolf Harris, say that they like a smooth painting surface because they like their brush to move freely across it. When they come to paint that sudden, inspirational and gestural brush mark it satisfyingly works first time and I totally understand. I would not have to keep going back for more paint if I too painted on a smoother surface, like an MDF board. I could, in the early stages, go one grade down from a coarse brush, to a cloth held over my finger (which holds even less paint, see below), and then work on a smooth board to avoid this problem, but I do like the vibrant contrast one sometimes gets by dragging dry paint across just the tops of the canvas weave, leaving the cavities untouched; with a smooth painting surface that opportunity would be lost. Have a look at the dappled light on the chest and forehead of ‘The Needle Woman’ by Velasquez as an example.

If you feel like a lot of experimentation, it is possible to get

any grade in between a coarse canvas and a smooth surface by gradually adding more layers of priming

to a canvas. Each successive layer of priming paint will fill up the cavities in the

weave a little more.

The other thing to bear in mind is that

canvas wrapped on stretcher bars has a tendency to bounce back at you

as you paint. If you don’t like this, remember that stretcher bars were

really invented so that artists would have a light load to carry when

they wanted to paint en plein air, but if you paint in a studio, and don’t have to

travel, then there is no reason why you can't just cut some canvas

off the roll and clip it to a piece of board to paint on. (Canvas bought by the roll always works out cheaper). As long as

you leave plenty of edge to spare you can then wrap it on stretcher

bars once it’s touch dried if you want to. I used to spend hours

wrapping canvases on stretcher bars but I no longer bother and it

saves a lot of time and effort.

Paint brushes and brush strokes

Artists who paint in oils tend to use either the coarse, hog’s hair (or synthetic equivalent) brushes, or the slightly softer brushes marketed as acrylic paint brushes. You can only use large watercolour brushes if you goo three quarters of its length up with oil, let it stiffen, and then just utilise the tip of the paint brush. If you use a large soft sable watercolour brush the way it was intended it will just bend as you apply pressure, though the smaller ones are fine for adding fine details in oils at the end of a portrait painting. If you like to do watercolour painting as well, then whatever you do, don’t put your watercolour paint brushes anywhere near an oil painting. Once you’ve got oil paint on your brushes it never really fully comes off again and it will wreck their capacity to absorb water.

The thing to appreciate about brushes is that the way you hold them greatly affects the job they do. Generally speaking a coarse haired paint brush holds less paint than a similar sized finer brush, so if you make a brush stroke with a coarse brush held perpendicular to the painting surface, yes, you will be applying a little paint, but mostly you will be spreading paint. If you then turn the brush so that it is held parallel to the painting surface and drag it along, then you are applying paint. If you hold a slightly softer acrylic brush, fully laden with oil paint and parallel to the surface and then drag it with reasonable pressure, then you will be applying a lot of paint and you can easily cover a thinly painted error. So to combat my deep canvas weave I change from a coarse paint brush to a softer acrylic brush about halfway through my painting and as I get more confidence I change the angle I am holding it at to increase the amount of paint I am applying.

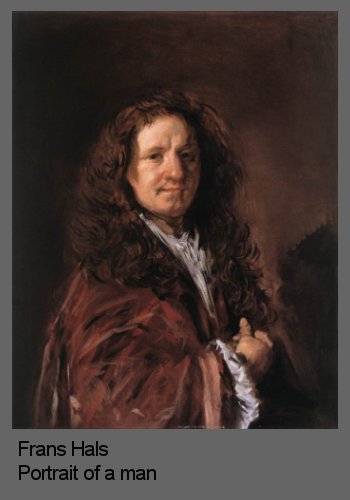

Ironically, far more important than how you hold a brush to put paint on, is how you take your brush off. Because take it off you must. As I said in the introduction to this page, if you don’t you will just start moving paint to places where you don’t really want it. Painters have to get into the habit of making a movement that puts their brush on and then off. The solutions that artists have come up with over the years to make sure they take their brush off their painting surface often manifest themselves very much as a signature artistic style. For example, Frans Hals, most famous for painting the portrait of the Laughing Cavalier, did a slashing movement and then took his paint brush off, George Seurat did a dot and then took his brush off and van Gogh did a long stroke and then took his brush off. I noticed that the portrait artist Robert Lincovitch, when doing a portrait of Billy Connoly on TV, held a long bristled brush parallel to the painting surface and oscillated it up and down a set amount

to prevent himself from straying away from his point of application (unless he specifically chose to). I had a go and it worked quite nicely; it produces quite a soft hazy style of painting. If you don’t particularly like your brush strokes to be seen, the way the portrait artist Ingres painted, for example, one way to achieve it is too do this brush oscillation and then blend the colours gently afterwards with a soft dry brush. Make sure you don’t overdo it though. Think very carefully about where you start or the portrait painting may end up dull and grey. If, on the other hand, you like the spontaneity of the visible brush stroke, have a go at loading the two sides of a brush with different coloured paint. Depending on the two colours you choose, this can produce a really vibrant effect and will always be tidier than trying to make two adjacent strokes with a tiny brush.

Summary

It takes artists some time to familiarise themselves with the properties of different painting surfaces, brushes and brush strokes. Hopefully recounting my experience above will help speed up the process for you. Most importantly, find a way to ensure that you take your paint brush off the surface to do your thinking, otherwise it will wander around with a mind of its own.

Remember that most painting surfaces, whether wood, board or canvas, will absorb oil paint over time, so it’s a good idea to prime them with something non-absorbent. Acrylic gesso or acrylic paint on its own are quite commonly used. Acrylic paint is basically just a plastic polymer that dries extremely quickly. This property can be useful, but don’t leave your priming brush lying around without cleaning it straight afterwards or it will be wrecked.

Did you like this page?

Copyright Fiona Holt, 2024